OPERATE COMMUNICATION SYSTEMS AND EQUIPMENT

DESCRIPTION

This unit covers the competency to transmit and receive communications in routine and operational situations using the organisation’s communications systems and equipment.

OBJECTIVES

On completion of this unit, you should be able to:

- Use appropriate communications systems and equipment

- Transmit and receive communications

- Maintain communications equipment relevant to sea kayaking

INTRODUCTION

Communicating seems to be an essential part of being human, and throughout history we have devised ways of extending the range of communication with signals, the carrying of written messages, and so on. Today we have fixed and mobile telephones, facsimile machines, radio, the Internet with email and VoIP (voice over Internet Protocol)... Within an organisation, their use is the realm of business systems.

In this module we are concerned with communications that can be used by kayakers at sea.

MARINE COMMUNICATIONS

Large vessels, commercial shipping and ocean yachts, carry HF radio and Inmarsat terminals, neither of which is practicable for kayaking. Our choices are between marine 27 MHz, marine VHF, and perhaps UHF CB. All three operate under class licences, so that individual licences are not required. However marine VHF users are expected to hold at least the Marine Radio Operators VHF Certificate of Proficiency (MROVCP) from the Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA).

The carrying of some form of marine radio may be required by state boating legislation: you should check local regulations and comply with them.

NETWORKS

State and territory authorities operate a network of Coast Radio stations as part of the national sea safety system for commercial shipping and other larger vessels. Limited Coast Radio stations are operated by commercial interests such as fishing companies, and volunteer sea rescue organisations.

Port authorities have their own stations for controlling shipping movements. Repeater stations have been set up along the coast to increase the effective VHF coverage.

They are sited on high points, and have a nominal range of 80 km, although that can be affected by ‘shadowing’ of high terrain. Repeaters re-transmit any signals they receive, and they are normally monitored by voluntary rescue groups. They use duplex channels, receiving on one frequency and transmitting on another.

Coast Radio stations operate 24 hours daily, but the Limited stations do not: they may be daylight hours only, and may vary their times according to season.The networks broadcast weather forecasts and other information according to schedule, and you should check the times and channels for the networks in your area

MARINE 27 MHZ

Marine 27 MHz is not the 27 MHz CB popular some years ago: the frequencies are different. For most boaters, this is the cheapest option. The range is sufficient for inshore or enclosed waters, and reception adequate although subject to atmospheric noise (‘static’) and interference from electrical systems. Marine 27 MHz is monitored by volunteer sea rescue groups, but not port authorities. Hand-held units seem to have been discontinued.

MARINE VHF

Marine VHF equipment is more expensive than 27 MHz, but offers clearer reception, free of interference. Over water, the range may be 10 nm or so, but is subject to shielding from cliffs and the like. In most areas there are repeaters to increase the coverage.

Several manufacturers offer hand-held waterproof transceivers small enough to fit a PFD pocket, and prices begin at under $400.

As noted above, operators of VHF equipment are expected to hold the Marine Radio Operators VHF Certificate of Proficiency.

Marine VHF is the only system that gives direct contact with port authorities and commercial shipping. There can be times when you will want to call an approaching vessel to alert it to your presence, for instance.

UHF CB

is not a marine system, however it is widely used in other activities and some volunteer sea rescue organisations monitor the calling and emergency channels, 11 and 5. As with the other systems, UHF is essentially line of sight, and on land there is a large network of repeaters to improve coverage. Reception is clear, with little interference. There is a wide range of transceivers available, some of them waterproof. As a public network, UHF CB is often undisciplined, and you may hear things that do not bear repeating. Commercial and organisational users often have private channels, outside the normal 40, for their own use to give privacy and avoid other traffic. For internal communications within an organisation, UHF may be an appropriate choice, but it cannot be used to contact marine authorities directly.

DIGITAL SELECTIVE CALLING (DSC)

Digital selective calling is a semi-automatic system of calling by transmitting coded information. Its advantage is that it automates the transmission and reception of emergency calls. Although DSC is being introduced to Australian waters, no hand-held equipment has DSC capability.

TRAINING AND QUALIFICATIONS

The volunteer sea rescue organisations offer training in a variety of marine subjects, including radio use, and can conduct examinations for the Marine Radio Operators VHF Certificate of Proficiency.

Alternatively, you can download the Marine Radio Operators Handbook from the Australian Maritime College Web site for private study: . A print edition is also available. The Handbook contains material covering all systems used at sea, with items required for the MROVCP syllabus indicated with the symbol ●, and you should regard it as essential reading.

COMMUNICATING

Radio communications are terse, and to minimise confusion use procedural words, or prowords, as standard terms for frequently used requests, instructions and reports. For example, the proword ‘This is’ alerts a receiving station that you are about to identify yourself with a callsign. In this module prowords are shown in bold.

Appendix 1 is a list of marine prowords. You need to be fluent. (French was once the language of diplomacy and military communication, and this is reflected in a number of prowords, such as mayday from m’aidez. Others are securite, silence, and silence fini, all pronounced as in French.) Also designed to minimise confusion is the Phonetic alphabet, used in callsigns and whenever words need to be spelled out.

The alphabet, and the numerals, are listed in Appendix 2. Again, you need to be fluent. There are two periods of silence every hour, when the only transmissions permitted are for emergencies. For three minutes at the hour and half hour, listen, but do not transmit. (Your watch will need to be accurately set.) If you can hear other traffic, particularly the coast station you wish to communicate with, those stations should be able to hear your transmissions.

If you’re against a cliff or similarly shielded elsewhere you may need to move out into the open to communicate. Except in emergency, you may not transmit from the land. However, by climbing up the hill you will improve reception. Sometimes even holding the transceiver over your head may improve things. Morse code also influenced radiotelephony.

The Morse for letter R (dit-dah-dit) was used to indicate ‘OK, understood.’ The spoken equivalent was ‘roger’ in the previous version of the phonetic alphabet, now romeo.)

CALLSIGNS

Coast stations and licensed ship stations all have official callsigns: for example The Australian Volunteer Coast Guard station at North Haven (Adelaide) is VMR555. A vessel would normally identify itself by name and callsign, e.g. Misty VLW2345. Without a licence, you will not have an official callsign and will have to devise one. Unlike other craft, kayaks rarely have individual names, but you could use the type of kayak — Nordkapp, Greenlander, Mirage, Raider — as a callsign. It could be based on a club or business name: Blue Water 3.

Some sea kayakers have taken to using their car registration as call sign, partly to help authorities identify their cars in emergency.

CHANNEL CHOICE

At least one channel in each band is designated as the calling and emergency channel, used to begin exchanges and for all emergency calls. For marine VHF it is channel 16, and for marine 27 MHz, channel 88. Once contact is established, stations change to another channel, referred to as a working channel.

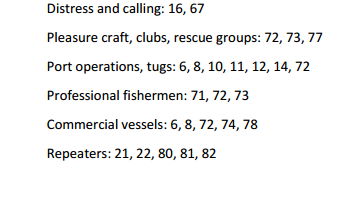

The standard channels are listed in Appendix 3. Similar procedures are used when contact is made through repeaters. If the two vessels are close enough, they will change to a standard channel after the initial contact to free up the repeater channel.

ROUTINE

Most of your calls will be to report your position or intentions, to request weather or tidal information and the like. Think about what you are going to say before you press the microphone key, and listen to make sure that you will not be intruding on another conversation. Speak clearly, at normal pitch, but a little more slowly than normal conversation.

Operators in shore stations may be in air conditioned comfort, but other listeners may have to contend with the sound of wind, wave, and in the case of powerboats, engine noise. If you are not sure you heard something correctly, you may ask the speaker to say again. If you repeat something yourself, begin with I say again...

Example

Vessel

Coastguard Oyster Bay, Coastguard Oyster Bay, Coastguard Oyster Bay

This is Voyager, Voyager, Voyager

Coast station

Voyager, this is Coastguard Oyster Bay. Go ahead

Vessel

Coastguard Oyster Bay, this is Voyager. Request current wind conditions

Coast station

Voyager, this is Coastguard Oyster Bay. Wind is 20 kn, gusting 28 from the north west

Vessel

Coastguard Oyster Bay, this is Voyager. Roger. Voyager out

Note that in the initial call the callsigns are repeated. If reception is good, especially with repeated exchanges, the repetition may be dropped. The proword over is rarely used, only if it is unclear that a reply is expected. It is the custom for the station beginning the exchange to end it, with out. If the stations had changed to a working channel they return to the calling channel to resume watch.

DISTRESS

Distress calls take priority over all other transmissions, and are used only when there is imminent danger to a vessel or persons requiring immediate assistance. The message begins with mayday, and includes the calling station’s callsign, its position, the nature of the emergency and the kind of assistance required, and any other information that may assist.

Example

Distress call

Mayday, mayday, mayday This is Scamp, Scamp, Scamp

Distress message

Mayday

This is Scamp

50 nautical miles due east Point Danger

Struck submerged object, sinking. Estimate time afloat 15 minutes. Require immediate assistance. 20 metre motor cruiser, red hull, white superstructure. Four persons on board. EPIRB activated.

If you are nearby and can assist, you are obliged to acknowledge the message, otherwise remain silent so as not to interrupt.

URGENCY

An urgency message is transmitted when there are concerns for the safety of a vessel or person, but no imminent danger of sinking or loss of life

Example

Pan pan, pan pan, pan pan

Hello all stations, hello all stations, hello all stations

This is Hawk, Hawk, Hawk

Position 34 degrees 9 minutes South, 134 degrees 42 minutes East. Lost propeller, drifting south east. Require tow.

Again, not much you can do except not interrupt.

If you are the one who has to make the call, perhaps with a medical emergency, make sure you are precise with your position and the nature of the problem.

SAFETY

Safety messages are generally weather or navigational hazard warnings, usually, but not always, transmitted by coast stations.

Example

Securite, securite, securite

Hello all stations, hello all stations, hello all stations

This is Darwin Radio, Darwin Radio, Darwin Radio

Gale warning. Listen on channel 72

After changing to the working channel, the station calls again:

Securite, securite, securite

Hello all stations This is Darwin Radio

Gale warning...

You do not need to respond, but perhaps take action.

MAINTENANCE

The equipment’s documentation will explain how to charge the battery and generally take care of things. Before use, you should check that there is sufficient charge in the battery, and that battery and antenna contacts are free of corrosion, etc. Other problems are likely to require work by an electronics technician.

After use, check the equipment again, and if it has not been in a waterproof bag, rinse and dry it before returning it to storage. Waterproof bags and other containers will also need regular inspections.

EXTENDED EXPEDITIONS

If you will be away for more than a day or so you will have to think about extra batteries, either fully charged rechargeables, or, if the transceiver can use them, sets of expendables. Some expeditions have carried solar panels to recharge their electronics.

OTHER SYSTEMS

MOBILE PHONES

Mobile phones are now almost ubiquitous in Australia, with coverage over most populated areas. For routine contact with home or business they are the system of choice. Check, however, that there is coverage in the area where you intend to operate.

In emergency you can dial 112 on a GSM phone to call emergency services, even if the phone has no SIM card or you are in another provider’s area. However, phones can be located only to their current cell, and it is therefore difficult to locate positions precisely, especially if you are offshore in a large cell. It’s not possible to ‘home’ on the signal, as can be done with VHF or 27 MHz signals.

SATELLITE PHONES

If you will be operating outside the coverage of other systems, satellite phones may be your only means of contact. With at least one carrier in Australia, conventional GSM and satellite communications are available in the same handset.

For routine use, satellite communications are still too expensive.

EPIRBS

EPIRBS,emergency position indicating radio beacons, are rugged, waterproof transmitters. There are several basic types, with the one carried in most outdoor pursuits such as kayaking and bushwalking being small enough to fit in a LIFEJACKET or clothing pocket

The beacons transmit a digital signal on 406 MHz, which includes the beacon’s identity. The signals are received by satellite and relayed via ground station to search and rescue organisations, which can identify the vessel, contact its owners or agents, and begin a search. The satellite can give a rough position, to within about 2 – 5 km, or within metres if the beacon includes a GPS receiver. Some EPIRBs also transmit a 121.5 MHz signal which searching aircraft can then home on to. In Australia, a beacon can be detected within an hour of being activated. Before carrying an EPIRB on any outing, check that the battery is within its expiry date, and that the beacon is undamaged, with its safety seal intact. Select Test mode and check that the indicator light is flashing, and that any audible signal (if the beacon has one) is present.

Some state marine authorities require that small craft carry EPIRBs, and you should check your state regulations. There have been cases in Australia where sea kayakers have used EPIRBs to call for assistance, with at least one being in a life-threatening situation. Remember, however, that an EPIRB is a last resort, to be used only if you cannot make contact by other means.

REFERENCES

Australian Maritime College, Marine Radio Operators Handbook, 2006, available from www.amcom.amc.edu.au/handbook

Australian Communications and Media Authority: www.acma.gov.au

Australian Maritime Safety Authority: www.amsa.gov.au

AMSA EPIRB information: Australian Volunteer Coastguard Association: www.coastguard.com.au

SATELLITE TELEPHONES

globalstar: www.globalstar.com

Iridium: www.iridium.com

Inmarsat: www.inmarsat.com

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This resource module was written by Peter Carter (MROVCP 5001626).

APPENDIX 1: MARINE PROWORDS

Affirmative Yes, true, correct, request granted.

Mayday Spoken three times: Urgent, life-threatening situation

Negative No, false, incorrect, request denied.

Out Used at the end of an exchange. It is customary for the station initiating the exchange to conclude it.

Over Used to end a transmission, and invite the recipient to respond.(Note that ‘Over and out’ is a contradiction.)

Pan, pan Spoken three times: Used to begin an urgency message.

Radio check Used to request a report on signal strength and clarity. If not addressed to a particular station, anyone may respond. The standard responses are: 1 bad, 2 poor, 3 fair, 4 good, 5 excellent.

Romeo/Roger Received and understood

Say again Used to ask the sender to re transmit (e.g. if the message was indistinct or interrupted). The response is ‘I say again...’

Security (Say-cur-Italy) Spoken three times: used to introduce a safety message.

Silence (See-lonce) Spoken three times: Cease all transmissions immediately. Silence will be maintained until lifted. Used to clear routine transmissions from a channel only when an emergency is in progress.

Silence fini (See-lonce fee-nee) Silence is lifted. Normal traffic may resume.

Stand by The receiving station should wait for further transmission from the sender, and acknowledge to the sender that they will do this.

This is This message is from the station whose callsign follows immediately.

APPENDIX 2: PHONETIC ALPHABET LETTERWORD PRONUNCIATION

NUMERALS