Kayak Sailing

OVERVIEW

The use of sails on sea kayaks to assist with longer passages has been common for decades. There are about as many different methods, types and variations of sea kayak sails and methods of sailing with sea kayaks, as there are different types and variations of sea kayaks. Rigs range from old beach umbrellas (the ‘Mary Poppins spinnaker’), to high-tech parafoil kites and everything in between.

This resource does not set out not to mention all the different types of sails and sailing methods, but rather to touch on some basic sailing terminology, to look at some of the more common methods of kayak sailing, and outline some of the valuable outcomes of sailing.

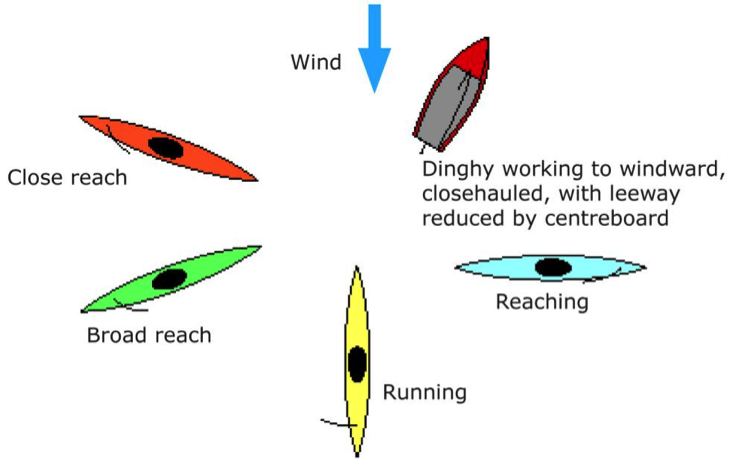

Sailing has specific terms for the directions of travel in relation to the wind. Each direction has a name:

The three main directions are down-wind, across the wind and into the wind, called running, reaching and beating.

Running is down-wind within about 30° either side of directly down-wind.

Reaching is travelling perpendicular to the wind but includes some travel into the wind (a close reach), and some travel down-wind (a broad reach). For kayaks, these are the usual directions.

Beating, or working to windward, is sailing into the wind. Without the centreboard or keel like that of a dinghy or yacht a kayak will not point very far into wind.

Outriggers and other devices like Bruce foils are sometimes fitted to kayaks, but these are beyond the scope of this reference, as are the dinghy-type rigs, with leeboards, fitted to some folding kayaks.

A number of manufacturers offer rigs for double and single sea kayaks. Many paddlers make their own rigs. (Some may have the sails themselves made professionally.) Besides the rigs shown here, paddlers have experimented with many others, such as lateen, genoa, and Ljungstrom. There are also kite sails, both factory and home-made.

Whatever the rig, single or double kayak, sailing enables kayakers to use some of the freely available energy of the wind, to save their own energy, increase speed and distance covered, and to add interest and excitement.

SAIL DESIGN AND CONSTRUCTION

The cloth used can be genuine sailcloth, or any other non-stretch, synthetic cloth or plastic film. Shower curtain material was used for early attempts (and has been used for crossing Bass Strait).

Masts can be made from any rigid tube, with aluminium the usual choice. Modern fishing rods are tapered composite tubes, and with the line guides removed, can make an ideal mast and boom.

The shape of a sail determines the complexity of construction. If you are attempting to build your own sails keep the KISS principle in mind.

Any design should be quick and easy to rig and unrig. Minimise lines and their length to reduce the likelihood of entanglement. The rig must float, achieved by sealing the ends of the spars. To maintain forward vision, a transparent window in the sail can be useful.

The three main types of sail used in Australia are the original Tasmanian rig, the Flat Earth Sail (based on the Norms’l), and the V-sail (Pacific Action Sail). The latter types are available commercially, and are generally designed to be easy to install. The step for the Tasmanian rig must be placed to suit the paddler’s reach, and requires a hole through the deck. All rigs require leads and cleats, with the cleats placed where they are easy to reach, but not likely to snag clothing.

Some key design questions to consider include:

- Running and reaching: Does my rig do both? Do I want to do both?

- Rigging and de-rigging: Can I set it up and pull it apart on the water in a range of wind and sea conditions?

- Sail shape: Is the majority of the surface area lower to the waterline or high up the mast? (This will greatly affect the stability of the kayak when sailing)

- Mast type and positioning: How will it affect my paddling and the kayak’s overall performance? How is it fastened to the deck? Is it a free-standing mast?

- Sheets (lines for controlling the sail): One sheet or two? It’s handy to only need one hand to adjust the sail.

- Stowing: Can I stow my sail rig (including the mast) effectively when not in use and while on the water? Is it lightweight, compact and durable?

Always test your rig for the first time in controlled situations. That includes capsizing and either rolling with the sail, or jettisoning it first.

A group sail rig may be constructed with anything you can hold up and catch wind: umbrellas, laminated charts (don’t lose your only chart), raincoats, tarps, etc. Make sure everyone is able to hold everything together comfortably: in heavier conditions the forces involved in keeping boats together are considerable.